第七届英国剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节2022

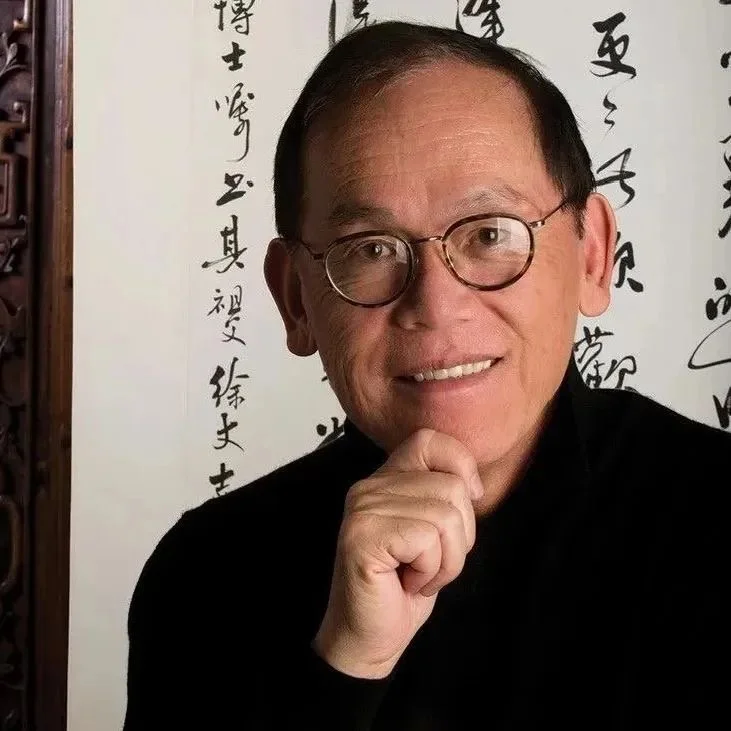

第一期节目——“名家有约:对话徐善曾”

编者按

转眼已经跨入了2022年,在这里,我们先祝大家新年快乐!

新年伊始,我们也将迎来第七届英国剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节的第一期节目——“名家有约:对话徐善曾”。徐善曾(Tony Hus)博士,是中国诗人、剑桥大学国王学院校友徐志摩(1897-1931)的长孙,他将与大家谈谈他眼中的祖父。

徐博士是徐志摩和他第一任妻子张幼仪的嫡孙,6岁起就举家移民到了美国纽约生活。自2014年剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节发起以来,徐博士携徐志摩家族的后人们多次远赴重洋,从美国来到英国,亲临剑桥参与活动,给予了很大的支持。

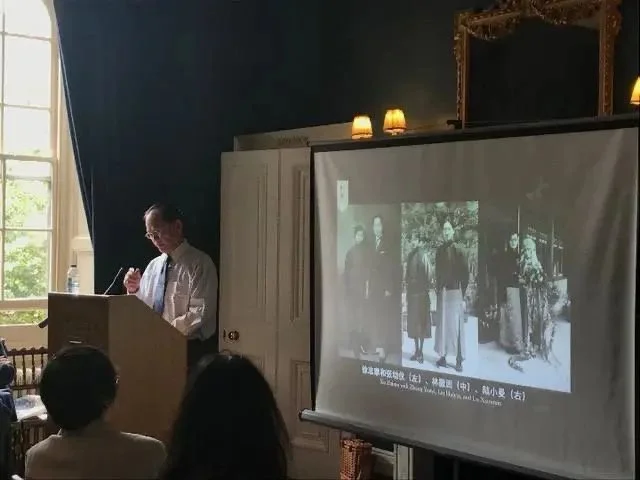

2016年第二届剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节徐善曾在剑桥大学国王学院院士花园举办新书发布会

虽然未曾见过祖父,但多年来,徐善曾始终对这位中国家喻户晓的诗人抱有敬意和好奇。徐志摩丰富的留洋经历、多彩的精神文化生活,造就了他前卫的思想境界,以及虽然短暂但传奇的人生故事,也让他的作品充斥着浪漫与情怀。

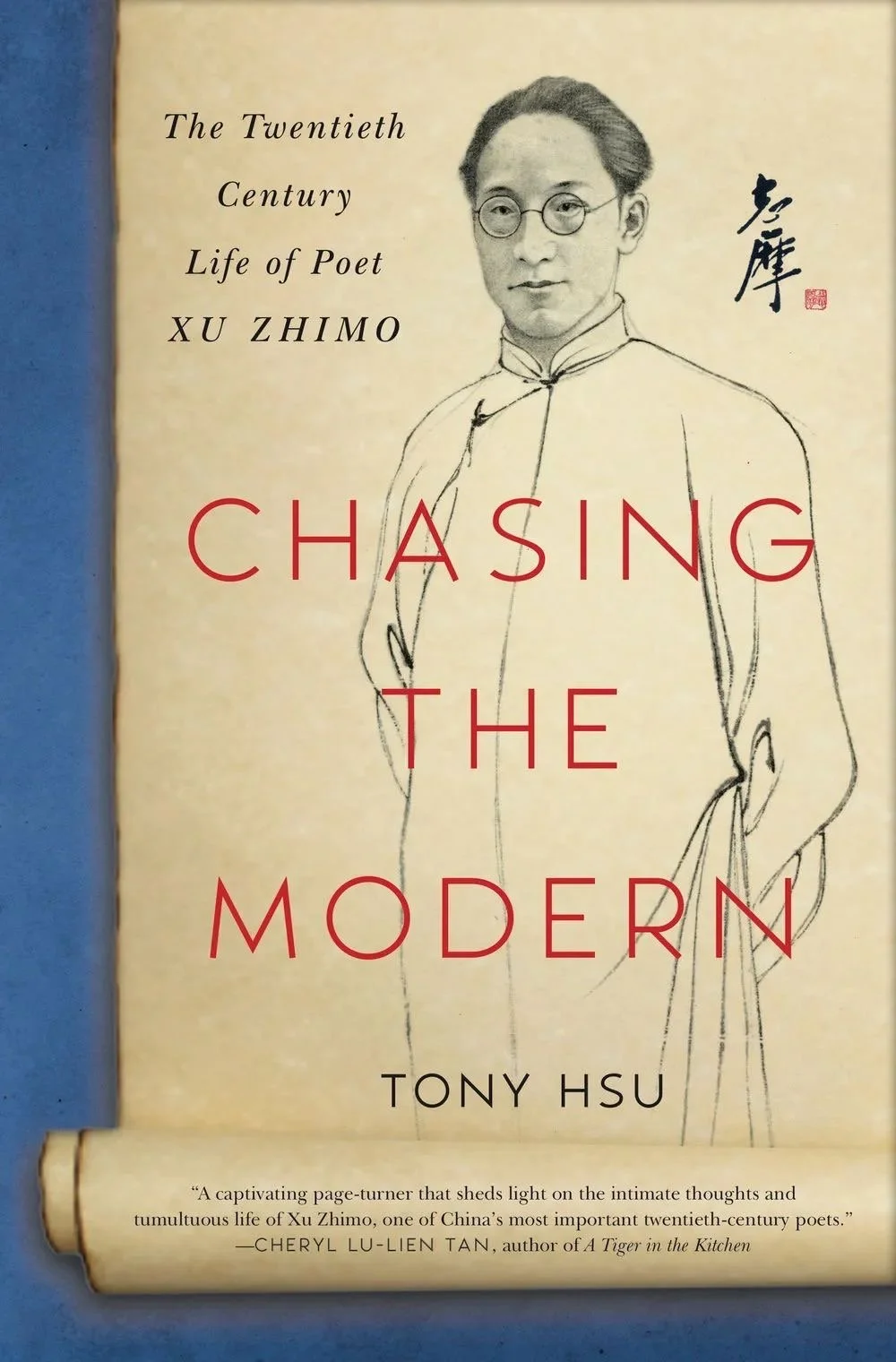

为了让世人更加走近徐志摩的文化与精神世界,徐善曾博士花了5年的时间,带着妻女游历世界各地,走遍了三大洲八大国,追寻祖父徐志摩的生活足迹,并将它们记录下来,写成了徐志摩的全新传记——Chasing the Mordern,由英国剑桥康河出版社联合出版发行。其中译版本《志在摩登-我的祖父徐志摩》,由中国中信出版社出版。

这本传记着眼于徐志摩人生定位的转换,以及他将自己定位为诗人后的种种努力和成就等历史过往。徐志摩笃定地坚持自己的现代理想,在他成就自己事业的同时,也伤害了自己的父母和结发之妻张幼仪;但在爱情理想破灭后,他又依然保持着知识分子的体面,也尊重和帮助摩登女性和知识分子,还挑起生活的重担。这虽然让他英年早逝,但也成就了他的诗名流传。

那么接下来,就让我们一起来听听徐善曾博士写作这本书的心路历程,以及在他的眼中,他的祖父徐志摩是一个怎样的人。

Chasing the Mordern 英文原版封面

这篇文字内容,源于2016年剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节期间,徐善曾博士做的演讲。徐博士在当年的诗歌艺术节期间,特别推出了他的新书《志在摩登》,并在剑桥大学国王学院的院士花园中,举办了新书发布会。著名中国诗人北岛、杨克、欧阳江河,著名中国艺术家刘正成、于明诠、李晓军等,和其他来自世界各国的近百位诗人、艺术家、学者和社会活动家,出席了新书发布会。

徐博士2016年剑桥诗歌艺术节期间发表演讲《志在摩登》

第七届英国剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节第01期 名家有约 首期访谈嘉宾 徐善曾(Tony Hsu)

徐善曾,徐志摩的嫡孙,二战后不久生于上海。他刚出生不久,父母就到美国留学,由他的奶奶张幼仪(徐志摩的第一位妻子)抚养他与几位姐姐。二十世纪四十年代末,张幼仪带着孩子们离开大陆来到香港。徐善曾在6岁时与姐姐们一同移民纽约与父母团聚,开始了在美国的新生活。

幼年时的徐善曾与祖母张幼仪和三位姐姐合影

徐善曾本科毕业于密歇根大学电子工程专业,后获耶鲁大学应用物理学博士学位,目前在数家科技公司任高管职务。

徐博士现生活在美国南加州,妻子包舜如是一位时装设计师,女儿徐文慈是一位导演与制片人。关于祖父徐志摩人生的《志在摩登》(Chasing the Modern),是他出版的第一部著作。

2018年,徐志摩的二十几位后人来到英国参加剑桥诗歌艺术节及“徐志摩花园”开幕式

{ 徐善曾谈他的祖父:诗人徐志摩 }

徐善曾Tony Hsu

我会在今天的谈话中,引用一些我书中的选段来继续我们的对话。

艾伦·麦克法兰教授,感谢您为我的书撰写的精彩序言,以及在书中传达的期许。能在我祖父传记的开头附上您如此深刻的见解,我感到万分荣幸。虽然我在2016年剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节之前几个月,就完成了《志在摩登》,但我还是选在诗歌艺术节上期间首次推出这本书,希望以此来纪念我祖父与剑桥的深厚情谊。

我已经连续多年回到剑桥,参加剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节。每一年与我们热情的东道主和所有促成这次活动的工作人员再度重逢,是一件非常美妙的事情。感谢您邀请我们回来。

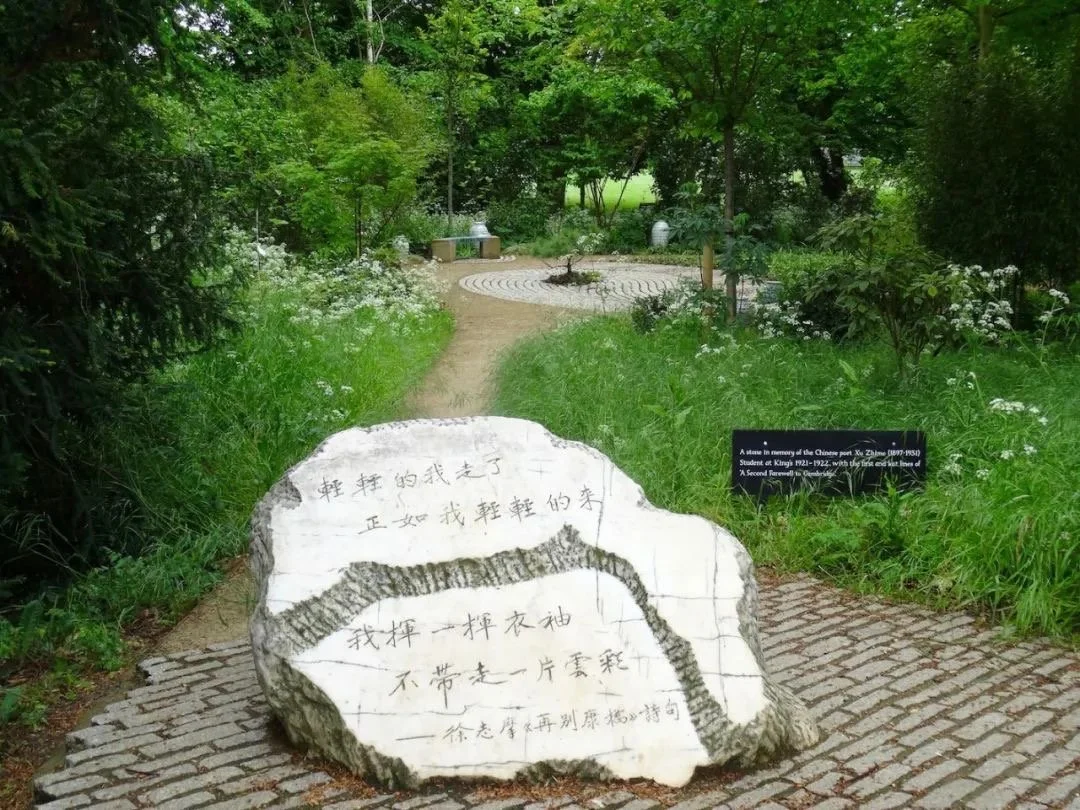

我想从我祖父最受欢迎、最重要的诗作——《再别剑桥》的精华部分开始。在2016年剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节期间,中国诗人北岛非常富有表现力地朗诵了这首诗。我现在仅朗诵四句,以开启我的发言:

“悄悄地我走了,

正如我悄悄的来;

我挥一挥衣袖,

不带走一片云彩”

徐善曾与其他参与2016年剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节的诗人学者们合影留念(后排左三:诗人北岛、后排左四:诗人欧阳江河)

“剑桥岁月”最能激发诗性

在我祖父35年的人生中,从1910年代末到1920年代年间,他都在世界各国游历,国际旅行在当时的中国人中,是极为少见的。

1918年,我21岁的祖父徐志摩第一次阔别家乡,离开中国,登上了一艘开往美国的远洋邮轮,赴马萨诸塞州学习,之后又在纽约哥伦比亚大学学习历史、经济学和政治学。他认为这将为他未来的商业之路打下坚实的基础。他想要协助建立国家银行体系,成为中国的亚历山大·汉密尔顿(Alexander Hamilton)。

同一时期,很多中国人和他一样就读于哥伦比亚大学,其中也不乏许多女性。1920年,他乘船前往英国,希望追随伟大的哲学家伯特兰·罗素(Bertrand Russell)学习。在英国,这位年轻的中国男子穿着飘逸的丝绸长袍,说着流利的英语,在夜晚自在地喝着鸡尾酒。他很容易就被当时许多伟大的英国作家和哲学家所接纳。作为一名生活在伦敦的年轻人,他的社交生活是与作家、学者一起度过的,E·M·福斯特(E.M.Forster)和托马斯·哈代(Thomas Hardy)都是他的朋友。当时,他的文化生活丰富多彩。之后,他有幸去了印度,并在那里写诗,也游历了法国、德国、意大利、美国和日本。

当这位30多岁的成熟男子回顾自己的一生时,提到,1921-1922年在剑桥的那段岁月,是他最快乐的时光。只有在国王学院做访问学生时,他的生活才是纯粹且真正快乐的。他每天花好几个小时阅读和写作,常常望着康河上方那被他称为“大自然的花束”的浮云出神。这是他第一次找到自己的声音、灵感的地方,在这里拥有了成为诗人的勇气。

剑桥对于我和我的三个姐姐——也就是徐志摩的孙辈来说,也是意义重大的。

1928年,他在第三次也是最后一次拜访这所大学后,写下了一首诗。他希望通过这次旅行能够重新找回他在大学读研期间所获得的灵感和纯粹的快乐。最后一次的剑桥怀旧之旅让他感动不已,他在从他的最后一次海外旅行——印度回程的船上写了一首诗。

康河与国王学院中的康桥

萌生写作传记的念头

正是我的祖父对剑桥的深刻回忆,促使我花了四年时间来撰写这本传记。多年来,我一直在考虑写一本关于祖父的传记,但这样的想法似乎遥不可及。

2011年,在访问剑桥时,我看到了国王学院2008年为祖父修建的纪念诗碑,这是艾伦·麦克法兰教授和在剑桥的其他人努力的成果。这块石碑坐落在康河的河畔。石上有四行中文诗。

当石头最初出现时以及之后的几年里,都没有任何标识来解释它的存在,这是故意而为之的。在到访过剑桥大学的中国人看来,很显然,这些文字便是来自祖父的《再别康桥》。但对于一般的非中国籍游客来说,这就是一个需要发现和探究才能理解的大谜题。剑桥大学希望这块没有说明的中国石头能激起人们的好奇心,激发他们去寻找他的作品,了解他在剑桥的时光和生活。

这块石头出现于2008年,是祖父在国王学院学习的86年后,也是他去世的77年后。我搜寻了剑桥的书店,想要找到更多关于他在剑桥生活的讯息,但令我惊讶的是,几乎没有关于他的英文著作,这让我开始考虑为他撰写一本传记。

剑桥大学国王学院里的徐志摩诗碑

2012年,麦克法兰教授问我是否可以写一本关于我祖父生活的小册子,一本包装精美的小书,短短几页就可以让剑桥的游客深入了解这位被这块石头授予荣誉的人。我非常乐意。所以,如果你翻开这本书,你可以想象接下来会发生什么。俗话说,“如果你想让上帝开怀大笑,那就制定一个计划”。一开始,我只是想写一本小册子,后来演变成了四年里,我带着妻子和女儿游历了3大洲,8大国,寻觅我祖父的踪迹。

在这些年里,我阅读了祖父中国传记的译本,以及在中国、英国甚至日本的中国文学学者和专家发表及未发表的论文。我参观了剑桥大学的一些办公室,和麦克法兰教授一起爬上了国王教堂的屋顶。我去了印度的加尔各答,在泰戈尔以我祖父的名字命名的茶馆里喝了茶。当我参观泰戈尔在那里创办的大学时,我受到了当地学生和教授们的热烈欢迎。就好像自从我祖父上次来访后,这片土地便在那一刻像被冻结了一样鲜少有人问津。

追寻祖父的终其一生的向往

为了追寻祖父当年的生活,我甚至骑着一辆破旧的自行车沿着剑桥的鹅卵石街道,顺着康河一路而下。我的向导是一位精力充沛的中国研究生,他说如果我们想跟随我祖父的足迹,我们就得去拜访格兰切斯特,那是我祖父最爱去的地方,他经常与国王学院的其他著名诗人和布卢姆斯伯里社团的成员一起聚会。

我借了一辆自行车,但结果不尽人意。我像疯了一样蹬着踏板紧追我的向导(他骑的很快!),突然,前方出现一对老夫妇,我不得不紧急调转方向,而这时自行车的刹车却失灵了。唯一能停下来的办法,就是撞向一片荆棘丛中,这让我受了点伤。

让我感到些许安慰的是,在这次旅行中,我看到了康河的三个部分:郁郁葱葱的树木和沿河美丽的草地小丘;河上漂浮着几艘平底船,学生们坐在河岸边野餐。我可以想象,在我祖父的时代也是这般场景,只希望他的自行车刹车没有失灵!

当我最后更深入地了解了我的祖父,以及他所代表的理想(有些人会认为他是为之而死的)时,觉得身上受到的所有伤痕都是值得的。这让我意识到,我不能单单写一篇简单的记叙文或是传体。我不能发表一篇仅仅只是简单陈述他的成就和家庭,却不涉及他生命中灰色地带的文章。因为在我的研究过程中,我感受到我的祖父是一个活生生的存在,围绕着他的个人哲学和许多他所做的复杂且困难的决定而引发的那些争议,也是如此。

众所周知,在徐志摩的有生之年里,他是中国最杰出的诗人之一。但你也许不知道,在一个政局动荡的时期,他不仅突破了中国文学的界限,还将自己的一生奉献给了对现代文学的执着追求。他年轻时花了很多年的时间仔细研究他成长时期旧中国的社会标准。这些与自由、个性和探索的现代原则相悖的规则,被他大胆地拒绝了。对他来说,实现自己的理想意味着做出艰难的选择,做出令人心碎和残酷的决定。

最典型的例子,就是他对待第一任妻子——我的祖母的方式。在他18岁的时候,他顺从父母的意愿,与我年仅15岁的祖母有了包办婚姻。对此,他感到很不高兴,甚至直接称她为“乡巴佬”。23岁时,他已经在西方独自生活和学习了3年,而他的妻子和他们的第一个儿子留在了中国。这是他们之间滋长着的身体和情感的纽带。

在英国的这些年里,或许是受到了罗素(Russell)几次联姻的鼓舞——罗素结了4次婚,在丑闻中离了3次婚,他意识到,如果他要成为一个真正的当代男性,他就不能被圈在包办婚姻中。无论他对妻子的感情有多深,这都是一场基于守旧传统的被迫结合。

作为一名先锋男性,他决定追求富有激情且自由的婚姻。那时,他已经爱上了别人。她是一位中国外交官的女儿(林徽因),与他同时期居住在伦敦,但问题是他还处在已婚的状态。那时候在中国,合法离婚还是闻所未闻的。

当徐志摩的妻子决定搬到剑桥和他在一起时,情况变得更糟糕了。当他在码头见到她时,他对她很冷漠,甚至以轻蔑的目光迎接她。二人在剑桥附近的一间小屋安顿下来后,他几乎立刻就开始秘密行事,每天早上都去理发或者办些其他什么事,至少他自己是这么说的。事实上,他是去邮局给他挚爱的情人寄信,并查询是否有收到她的来信。就这样几个月后,他再也无法继续过这样的双重生活了,他告诉妻子他不想再维持这种婚姻。他想要表达的是,作为一个新时代男性,他不能继续生活在包办婚姻当中。

在剑桥那段令人忧心的日子里,有一天,他消失了,再也没有回来。他想方设法搬进了剑桥的一间宿舍。在这个节骨眼上,他的消失引发了几个大问题:他娶了我那几乎不会说英语的祖母,并且让她独自一人呆在了英国。而且,她还怀了他们的第二个孩子。

最终,祖母搬到柏林和哥哥住在一起,并独自生下了一个叫彼得的孩子。彼得出生后不久,我祖父找到了他的妻子,正式向她提出离婚。我想引用《志在摩登》这本书的一个章节“一个脱胎换骨的男人出现了”中的一段:

“就好像写了一份反对包办婚姻的宣言,他告诉她,他们毫无激情的婚姻不应该继续下去,真正赎回自由将让他们双方都看到生命的曙光。他宣称,不以浪漫爱情为基础的婚姻是无法容忍的。”

他为了说服他的妻子终止他们的婚姻,便邀请她到城里的一个朋友的家里去。当她到了那里,并看到他和一些中国朋友高兴地围站在那里时,她妥协了,也签署了文件。他说:“太好了,太好了,这太有必要了,中国必须摆脱老旧的模式。”所有的朋友看起来都很高兴,与他握手言欢,因他达成了中国历史上第一次现代离婚而欣喜。

在接下来的几年里,随着他的名声大噪,他具有突破性的离婚举动,将成为社会进步和自由的象征。这一大胆的婚姻关系的破裂,标志着中国婚姻从传统架构向更现代的西方式架构(包括个人幸福)的转变。同时,离婚也是切断与另一个人不必要联系的一种方式。因此,离婚对徐志摩来说意味着一种新的自由感,但也给他的结发妻子带来了困难。在书中接下来的几页中,读者可以发现,他的第二个儿子彼得在三岁时夭折了。这在很大程度上是因为他的妻子没有从他那里得到直接的经济支持,所以她没有能力支付医疗费用。

在我了解祖父的那些年里,有很多次我都希望我能紧紧抓住他的肩膀,摇一摇,告诉他控制住自己的情绪,我会告诉他,“你不能仅仅为了追求自己的理想而做这些事情”。

他做了很多有问题的决定,但我从来都不讨厌我的祖父,有时我甚至希望他能成为一个与众不同的人。我花了数年时间阅读他的文章,理解他的诗歌,仔细研究他的生活和历史背景,才真正走进他的内心,明白他这么做的意图。在这个过程中,我最终不仅原谅了他,而且尊重他,敬仰他。我意识到他是一个冒险者,一个边界推动者,一个有理想的人,一个有个性的人,他坚持自己的信仰,即便这样会伤害他和他身边的人。我从他所做的选择中学到了很多关于跨越信仰和忠于自己的东西。我明白了,我们不能用自己当下的标准,来评判过去某个人所做的决定。

与我的祖母离婚几年后,28岁的徐志摩邂逅了真爱,并且像一个现代男人一样步入了婚姻的殿堂。她是一位上流社会的已婚少妇,年仅21岁,是一名业余交际舞演员和社交名媛,以美貌和社交而有名气。他们二人都必须先和原先的配偶离婚才能结婚——这种情况在他们的家庭内部和整个中国社会引发了争议。对于诗人来说,为爱而结婚不仅是激情和自由意志的实现,也是一种政治立场。他从自己的生活中摒弃了包办婚姻的过时传统,在当时的中国树立了榜样,自己寻到伴侣也意味着永恒的幸福。

不过事实证明,他的第二次婚姻是一场巨大的灾难。他的新婚妻子很快就开始追寻自己所爱。这是书中第九章的内容:“克服重重困难,爱情战胜一切”。长期以来,她一直饱受心率不齐和疲劳的折磨,她紧张的表演日程安排更让她感到精疲力竭。

1927年春天,在结婚七个月后,陆小曼结识了一位业余演员,翁端午,他出身名门,家人是省级官员、画家和收藏家。他们在很多剧目中一起扮演主角。主演了几部戏剧之后,他们成为了好朋友。徐志摩也非常欢迎他来他们家做客。

一次难度特别大的演出让她卧床不起,翁端午就给她按摩,他声称这样的按摩可以让她痊愈。当时,徐志摩并没有意识到他们已经沉浸在恋爱当中了。翁瑞午还推荐她吸食鸦片,声称这有助于她的身体的循环,治愈她的疲劳。经过几次吸食,她成了一个瘾君子。每天吸食毒品不仅让她陷入梦幻般的状态,还削弱了她的创造力、才华和美貌。这种毒瘾把她和翁端午捆绑在了一起,两人常常一起吸食好几个小时的烟。

有一天晚上,我的祖父从大学教书回家,发现他们蜷缩床上吸食鸦片,却仍然希望陪伴着她,他躺在她的身边,而翁端午睡在另一边。第二天早上,徐志摩的父母进房,看到他们三人同床共枕的场面,感到难以容忍。

追溯我祖父的一生,我不仅了解了一个人的人生道路,还了解了文明,了解了一个人的命运如何随之起起落落。1931年,徐志摩在一次飞机失事中去世了,年仅35岁。当时,他已经是一位全国知名人士,也是同年龄段里最著名的诗人。他的家乡还在山上为他建了一座美丽的陵墓。

作品重见光明

在他死后的几十年里,尤其是文革的十年里,他的作品被视为是颓废的资产阶级的产物。过于放纵,只专注于浪漫的爱情,轻浮追求情感,这样的作品是新中国所不能接受的。因此,与其他许多作家一样,徐志摩的书籍、诗歌和散文被烧毁、填埋;他的墓地被摧毁,坟墓周围的树木被砍伐,周围的金色石头被扔出去用作砌城墙。

十年动荡的年代,湮没了徐志摩的遗留下来的文学作品。在他死后两代人的时间里,他就像从未存在过一样。直到1980年代初,徐志摩又再次迎来了光明。

如书中的第14章所述,1981年11月,一名高中教师在徐志摩逝世的50周年之际,前往他的墓地祭拜。在另一个地区生活了几十年后,这位老师又回到徐志摩的故乡海宁当地的一所中学教书。他听说徐志摩的坟墓被破坏了,但没想到被破坏的严重程度这么强。他儿时读过徐志摩的诗,看着眼前的废墟,他强忍住了眼中的泪花。

在这次拜访之后,他决定说服当地重建诗人的坟墓。他在墓穴附近的东山上找了几天,但始终没有找到墓碑。随后,他便去了铜山脚下的一家老茶馆,询问住在附近的一位农民。很快,他就从交谈中得知,墓碑已经被工人拿走了,其中的一些石块还被他们当作住所的材料使用。附近的村民说,这些石头被用作村舍和猪圈的基底。当地还征用许多石头修建桥梁和道路。几年之内,许多石头就从遗址上消失了,从所谓的反动作家的坟墓里被剥去。这些坟墓的石料被用以各种方式来重建现在的新世界。

据那位老师说,坟墓的状况让他倍感失望和沮丧。有一天,他听说有一个人曾经照料过徐志摩的坟墓,于是经过多方查找,他终于找到了那个被人们亲切称为李老头的跛足老人。这名老人能够辨认出墓碑所用的石头类型,他摇了摇头,说他不知道它们在哪里,但老师可以看出,这位老人在犹豫。他理解老人的反应,那时的中国依然处在从十年动荡年月中走出来的阶段——尽管那个时代在五年前就已经结束了,但人们还必须小心行事。对这位曾经遭到谴责的诗人表现出热忱,可能会给所有相关的人带来麻烦。

尽管如此,老师还是希望能获得解决办法,恢复诗人的坟墓和荣誉。之后,有一天早上,李老头派了一个学生到了老师任职的学校,说他有东西要给他看。

1981年12月9日,李老头带着老师去了一个村子,在村子南部的边缘有一个码头。他向村民们打招呼,指着码头问道:“这就是你要找的东西吗?” 他们向下看去,只见一大块石头上覆盖着泥土,李老头让一群人把石头翻过来。老师说,当时的他站在那里发自内心地祈祷。当石头被翻过来时,老师念出了上面的几个字“诗人徐志摩之墓”。

徐志摩家族前去海宁徐志摩墓祭祖

我可以很高兴地说,今天,志摩遗留下来的作品已经重新被恢复与发扬光大。他的作品已经在当代中国文学中占据了一席之地,他的诗歌也在中国大陆和台湾省的高中、大学中被广泛诵读。

2000年,来自亚洲各地的数百万观众观看了一部讲述他人生的大型电视连续剧《人间四月天》。2013年,中央电视台也播出了一部富有热忱的纪录片,讲述了他在世界各地的生活。另外,他的几首诗还被改编成了流行歌曲。

因此,尽管我的祖父历经磨难,但或许正是因为这样而让他变得家喻户晓。并且在他去世的85年后,我们在一年一度的剑桥徐志摩诗歌艺术节上举杯,向他丰富的文化遗产和他不朽的精神致敬。

那么,追随他写本书的这近5年来,我都学到了什么?我了解了是什么造就了一个传奇,也了解了为什么他的文化遗产能够经久不衰。除了与生俱来的天赋和才智,徐志摩的远见和性格几乎让每个人都产生了共鸣。他有一个不可动摇的信念,那就是通过诗歌和忠于自己理想的生活,他可以带领一个国家走出一个不合时宜的文化和信仰的黑暗时期,通过情感和自由进入到现代的光明大道上。

最后,我将用他的四行诗作为结尾:

“我是天空中的一朵云,

偶尔投影在你的波心,

你我相逢在黑夜的海上,

你有你的 我有我的 方向”

感谢各位的聆听。

Tony Hsu on his grandfather, poet Xu Zhimo

徐善曾在徐志摩诗歌艺术节上介绍祖父徐志摩

TH: I will read a couple of lines to get the feeling going. Thank you for the kind introduction, Alan, and also for your forward in my book. It’s an honour to have your insightful words at the beginning of my grandfather’s biography. Although I completed ‘Chasing the modern’ several months ago, I am debuting the book at this festival with hope to honour my grandfather’s deep connection to Cambridge. This is the third consecutive year that I have returned to Cambridge for the Xu Zhimo poetry festival. Each year it has been wonderful to reconnect with our gracious hosts and all of the hardworking individuals who make this event possible. Thank you for inviting us back.

I’d like to start with an abbreviated version of my grandfather’s most popular and important poem, ‘A second farewell to Cambridge’ which was eloquently cited last night by Ben Dao. I am only going to read four lines; ‘Quietly as I am leaving, quietly as I came, I shake my sleeve not to bring away a patch of cloud’. During my grandfather’s 35 years of life, he travelled all over the globe in the late 1910s and 1920s, international journeys were a rarity among the Chinese at the time.

He first left his home in China in 1918 at age of 21, boarding an American bound ocean liner to study in Massachusetts and then Columbia University in New York where he studied History, Economics and Political science which he believed would prepare him for future business. He wanted to become the Chinese Alexander Hamilton by helping to establish a national banking system.

A lot of Chinese people were at Columbia at same time as him, and also many women. In 1920 he sailed to England to study with the great philosopher Bertrand Russell. In England, this young Chinese man in the flowing silk robe, now fluent in English, and comfortable in evening cocktail drinks. He was easily embraced by many great British writers and philosophers of the time. As a young man in London, his social life was spent with writers, scholars, Ian Forster and Thomas Hardy were among his friends. There was a very rich culture at that time. Later in his life he had the privilege of writing poetry in India, he travelled throughout France, Germany, Italy, America and Japan.

As a grown man in his 30s looking back at his life he declared that his Cambridge years, 1921-1922 had been his most joyful time. Only while at Kings College as an independent study student was his life was natural and truly happy. He spent hours reading and writing. He watched the drifting clouds above the River Cam which he called nature’s bouquet. Cambridge has come to mean so much to my three sisters and me: his grandchildren. This is a place where he first found his voice, his inspiration and courage to become a poet.

He wrote poetryin 1928 after his third and final visit to the university. His hope for this trip was to rediscover the inspiration and pure happiness he had found during his graduate student days at university. Moved by his final nostalgia-tinged visit to Cambridge, he wrote a poem while on a ship from India, his last overseas journey. It was my grandfather’s profound recollection of Cambridge that moved me on a four-year journey to write this biography. For years I considered writing a biography on my grandfather but doing so never seemed quite within reach, then on a visit to Cambridge in 2011 I laid eyes on the memorial stone in King’s College erected for my grandfather in 2008 as a result of the effort of Alan Macfarlane and others in Cambridge. The stone sits on the edge of the River Cam. The stone bears four lines of poetry in Chinese and when the stone first appeared and for several years afterwards, there was no signage explaining the stone’s presence which was intentional. To the Chinese speakers who visited the university, it is clear that the text came from his second farewell to Cambridge, but to the average non-Chinese traveller it was a glorious mystery which one had to discover and investigate to understand. The university hoped the Chinese stone without description would pique curiosity and would inspire them to seek out his work and become acquainted with his life and years in Cambridge. The stone appeared in 2008, 86 years after he studied at King’s college and 77 years after my grandfather perished. I searched the Cambridge bookstores to find more about his life and to my surprise there was little written about him in English, and this got me thinking about writing his biography.

In 2012, Professor Macfarlane asked if I could write a short account of his life, a glorified pamphlet. A few pages that would give Cambridge visitors insight into the man honoured by the stone. That was something I was willing to do. So, if you take a look at the book, you can imagine what happened next. The old saying; ‘If you want to make God laugh, make a plan’. What began as an attempt to write the pamphlet morphed into a four-year odyssey of me travelling all over the world with my wife and daughter to 8 countries on 3 continents in search of who my grandfather was.

During these years I read translations of Chinese biographies, published and unpublished theses of Chinese literature scholars and experts in China, England and even Japan. I visited Cambridge offices, climbed up the rooftop of King’s chapel with Professor Macfarlane. I travelled to Calcutta and had chai in the teahouse that Tagore named after my grandfather. When I visited the university that Tagore had founded there, my father and I were enthusiastically welcomed by students and professors, it was if the grounds has been frozen in time since my grandfather had last visited.

In pursuit of my grandfather’s life, I even took an ill-fated bike ride down the cobblestone streets of Cambridge down alongside the River Cam, my guide was an energetic Chinese grad student who said that if we sought to follow my grandfather’s trail, we would have to visit Grantchester, a favourite hangout of my grandfather who socialised with other well-known poets of King’s and members of the Bloomsburg group. I borrowed a bicycle, and the result wasn’t pretty. I pedalled like a madman to catch up to the student and when an elderly couple appeared, I had to swerve, and the brakes of the bike came out. The only way to stop was to crash into a large thorny bush. It was some consolation that during this trip that I got to see three sections of the River Cam, lush trees and beautiful grassy knolls along the river. There were a few punts on the river and students having picnics along its banks. I could imagine it being the same in my grandfather’s time and could only hope his bike had brakes! In the end all the bruises and cuts were worth it as I learned more about who my grandfather was and the ideals he stood for, and some would argue died for. I knew I couldn’t write an easy narrative or biography. I could not publish something that would simply cover his accomplishments and family but offered no entrance to the grey areas of his life. Because during my research my grandfather came alive for me and so did the controversies that surrounded his personal philosophies and many of his complex and vexing decisions. As many of you know, during his lifetime, he was one of the most prominent poets living in China. But what you might not know is that as well as pushing boundaries of Chinese literature during a time of intense political chaos, he also devoted his life to the single-minded pursuit of the modern. He spent many years of his young life scrutinising the archaic social standards of old China in which he was raised. It was these standards, which didn’t align with the modern principles of freedom, individuality, and exploration, that he boldly rejected. For him, living up to his own ideals meant making choices that were difficult and decisions that would prove heart-breaking and cruel. The biggest example is the treatment of his first wife, my grandmother. Bowing to his parents’ wishes, at the age of 18 he entered an arranged marriage with my grandmother who was 15, he was unhappy about it and went as far as addressing her directly and referring to her as a country bumpkin. By age 23, he had been living and studying in the West on his own for 3 years while his wife had been in China with their first son. This was something between them that saw a physical and emotional bond grow. During his years in England, perhaps buoyed by convos with Russell, who married 4 times and divorced 3 amidst scandal he realised that if he were to be a truly modern man he couldn’t remain in an arranged marriage. It was a forced union based on anachronistic dictates, no matter what affection he had for his wife. As a modern man he decided to pursue a marriage of passion and freewill instead. He had already found love with someone else. She was the daughter of a Chinese diplomat who was living in London as same time as him, the problem was that he was still married, and legal divorces were still unheard of in China. Things got worse when his wife decided to move to Cambridge to be with him, when he met her at the docks, he gave her no affection but greeted her with looks of disdain. The pair settled in a cottage near Cambridge and almost immediately he began acting mysteriously, leaving every morning to get his hair trimmed, or so he said. In reality, he was actually going to a post office to send and check letters from his lover who he had already fallen deeply in love with. So, after a few months he could no longer carry on with the double life and told his wife that he didn’t want to be married anymore. He hoped to express that as a modern man he couldn’t remain in the arranged marriage. One day during this fraught period in Cambridge, he disappeared never to return, he managed to move into a dorm in Cambridge. There were a few big issues with him disappearing at this point; he was married to my grandmother who could barely speak English and was alone in England and also, she was pregnant with their second child. She ended up moving to Berlin to live with her brother and gave birth to the child called Peter on her own. Shortly after Peter’s birth, my grandfather found his wife and asked her formally for a divorce. I’d like to read from a chapter of the book, ‘A new man emerges’; ‘And as if writing a manifesto against arranged marriages, he told her that their passionless marriage should not be allowed to continue and that to truly redeem their freedom would allow them both to see their life’s light of dawn. Marriage not based on romantic love he declared was intolerable’. He went on further to explain, for the purpose of convincing his wife to terminate their marriage, he asked her to come to a friend’s house in the city, when she arrived, she saw him and some Chinese friends standing around happy and she capitulated and signed the papers. he said ‘Wonderful, wonderful, this is necessary, China must rid itself of old ways’. All the friends looked glad and shook their hands and looked joyful he had just obtained the first modern Chinese divorce in history.

As his fame grew in the years to come, his ground-breaking divorce would become a symbol of societal progress and freedom, the audacious breaking of marital ties marking the transition of Chinese marriage from a traditional framework to a more modern Western style framework including individual happiness, but also divorce as a way to sever an unwanted connection to another person. So, divorce meant a new sense of freedom to Xu Zhimo but also brought hardship to his old wife, what the reader discovers in the pages that follow is that his second son Peter died at the age of three largely because his wife wasn’t getting direct financial support from him and couldn’t afford medical care. In the years I spent getting to know my grandfather, there were many times I wish I could grab him by shoulders, shake him and tell him to get a hold of himself, ‘you can’t do such things simply to pursue your ideals’ I would tell him. He made many questionable decisions, but I never disliked my grandfather, yet there were some moments when I wished he had been a different man. It took me years of reading his essays and absorbing his poems and poring over his life and the historical context to really understand him and his motivations. In doing so I ultimately came to not only forgive him but to respect him and even to admire him, I realised he was a risktaker, a boundary pusher, he was a man of ideals, a man of character and he adhered to his beliefs even if it hurt him and people around him. I learnt a great deal from the choices he made about taking leaps of faith and being true to yourself. I learnt that we can’t judge the decisions of someone in the past by our own contemporary standards.

A few years after divorcing my grandmother, at the age of 28 he went on to find love and enter a marriage as a modern man, she was a 21-year-old married high society doyen celebrated for her beauty and talent as an amateur ballroom dancer and a socialite. They both had to divorce their spouses to marry - a situation that stoked controversy within their families and in Chinese society at large. For the poet marrying for love wasn’t only a realisation of passion and freewill, it was also a political stance. He banished from his life the outmoded tradition of arranged marriage and set an example for all China, finding a match on his own would mean eternal happiness too. Reality turned out different, his second marriage proved to be a huge disaster. His new wife soon began following passions of her own. I am reading from chapter 9; ‘Against the odds, love prevails’; ‘She had long suffered from an erratic heartbeat and fatigue and her strenuous performance schedule would leave her fully depleted, in spring 1927 after seven months of marriage, she had become acquainted with an amateur actor, Wang, he too descended from high born cultured family, his family was a provincial officer, painter and collector. They sang leading roles alongside each other on many occasions. By the time the two had starred in a couple of plays they had become good friends. Xu welcomed him into their home. One particular strenuous performance left her bedridden, and he offered her a massage and she proclaimed that the treatment was healing to her, Xu didn’t realise that they had become romantically involved. He also introduced her to opium smoking claiming that it would aid her circulation and cure her fatigue. After a number of smoking sessions, she had become an opium addict. The daily smoking of the drug didn’t only lull her into a dreamlike state but also sapped her creativity, talent and her beauty, this addiction bonded her to Wang who shared the pipe with her for many hours. One night in fact, grandfather came home from teaching in university and found them curled up in the opium bed, still hoping to be with her, he laid next to her with Wang on the other side. The next morning Xu’s parents came in and found the three of them sharing the same bed, it was more than they could tolerate.

In shadowing my grandfather’s life, I learnt more than just about one man’s path, I learnt about civilisation and how one’s fortune and destiny can rise and fall and rise again. He died at the age of 35 in 1931 in a plane crash, before this he was a national celebrity and the most famous poet of his age. His hometown built a beautiful tomb in the mountains for him.

In the decades to come after his death, notably the 10 years of the Cultural Revolution, his works were declared decadent and bourgeoise, too indulgent and focused on romance and frivolous pursuits of love and sentiment that weren’t acceptable to the new China. So along with many other authors, Xu’s books, poetry and essays were burned and buried, his grave site destroyed by red guards, the trees around his tomb cut down and the golden stones around his grave hurled off to use for town walls. The ten-year period of the Cultural Revolution devastated Xu Zhimo’s legacy, for two generations after his death it was as if he never existed, in early 1980s, Xu Zhimo found the light again. As noted in chapter 14, in November 1981 a high school teacher travelled to Xu’s gravesite to pay his respects on the 50th anniversary of his death. After several decades living in another area, the teacher returned to teach at a local middle school and heard that Xu’s grave had been damaged, he wasn’t aware of the severity of the grave’s destruction. He had read Xu’s poem as a child and surveyed the wreckage and choked back tears. It was during this visit that he decided he would convince the city to rebuild the poet’s grave. So far days he searched the eastern hill near the grave to locate the tombstone but found nothing, he then went to an old tea house at foot of the Dong mountains to speak to a peasant who lived nearby. He soon learnt that the stone of the grave had been taken away by workers some of whom used them for their settlements. Neighbouring villagers said the stones been used to build the bases for cottages and pigpens. The local government had also appropriated many of the stones to build bridges and roads. Within years many of the stones had disappeared from the site, stripped from the grave of the so-called reactionary writer who lived in heyday of China as a new republic. They were put to use in a myriad of ways to rebuild the now Communist country. The teacher said the state of the grave made him feel disappointed and frustrated. One day he learned of the man who once took care of Xu’s grave and after many attempts he found the elderly and crippled man known affectionately as old man Lee. This man was able to identify the type of stones used for the gravestone, he shook his head and said he had no idea where they were, the teacher could tell the man was holding back, however. The teacher understood the old man’s reaction, China was still emerging from the Cultural Revolution - even though that era had ended five years before, one still had to tread lightly. To show passion for the once denounced poet could prove ruinous for all involved. Still the teacher hoped for a resolution, the restoration of the poet’s gravesite and his honour. Then one morning, old man Lee sent a student to the teacher’s school and said that he had something to show him, on December 9th, 1981, Lee took the teacher to a village, on the southern edge of village sat a dock. He greeted the villagers and pointed to the dock then asked, is this what you’re looking for? They looked downward and saw large slab of stone covered in mud and Lee asked a group of men to turn over the stone, the teacher said he stood there praying from bottom of his heart. When the stone was turned over the teacher read the words; ‘the grave of the poet Xu Zhimo’.

I’m delighted to say that today Zhimo’s legacy has risen from the tumult of the Cultural Revolution, his writings have taken their place in the literary canon of contemporary Chinese and his poems are read in high schools and universities in China and Taiwan. In 2000, millions of viewers from all Asian watched a major dramatization TV mini-series of his life titled ‘April rhapsody’. In 2013, CCTV aired an ambitious documentary of his life seen all over the world and to top this off several of his poems have been turned into pop songs. So, despite all that my grandfather endured and maybe because of it, his reputation continues to rise again and here we are 85 years after his death at the annual Xu Zhimo poetry festival raising our glasses to his legacy and his enduring words. So, what did I learn having followed him for almost 5 years to write this book? I learnt what makes a legend and why his legacy endured. Beyond his innate talent and intelligence, Xu Zhimo had a vision and character that resonated with almost every person he encountered. He had an unshakable conviction that through poetry and living true to own ideals he could lead a country out of a dark period of anachronistic culture and belief through emotional and intellectual freedom into a modern light. I will end by reading four lines; ‘I am a cloud in the sky, by chance casting a shadow on the ripples of your heart, you and I met on the sea at night, you had your direction, I had mine’. Thank you for listening. (End)